What is Dyslipidemia?

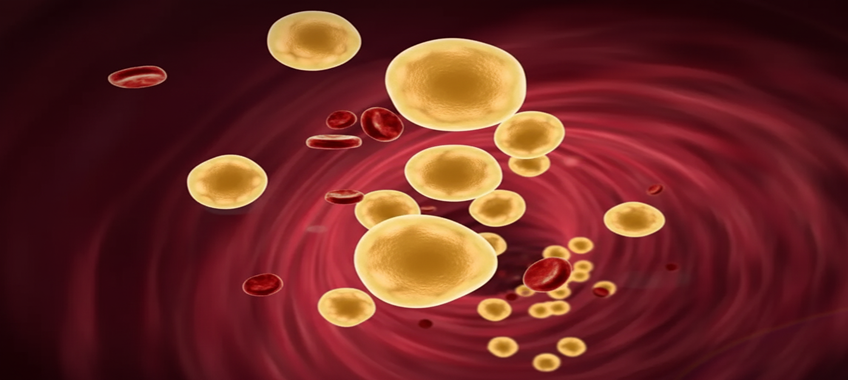

Dyslipidemia refers to an imbalance of lipids cholesterol and triglycerides in the bloodstream, which substantially raises the risk of cardiovascular diseases. It develops when lipid metabolism becomes disrupted due to genetic predispositions or lifestyle factors such as unhealthy diet and inactivity. Over time, excess lipids promote atherosclerosis, where fatty deposits build up inside arterial walls, restricting blood flow and increasing the likelihood of heart attacks and strokes.

Why It’s Dangerous?

The condition silently damages blood vessels long before symptoms appear. When low-density lipoprotein (LDL), known as the “bad cholesterol,” accumulates, it encourages plaque formation inside arteries. In contrast, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), the “good cholesterol,” helps clear LDL from circulation. When triglycerides rise usually due to extra calories that the body doesn’t burn they are stored in fat cells and released later for energy, but excessive buildup increases cardiovascular strain. This imbalance steadily turns into a threat that may go unnoticed until serious events occur.

Personal Experience and Clinical Insights

From my experience working with patients, I have seen how small changes in diet or physical activity can significantly influence lipid levels. The liver plays a crucial role, producing cholesterol necessary for hormone synthesis and digestion, but dietary intake particularly from red meat, dairy, and processed foods can easily push total cholesterol beyond healthy limits. When blood cholesterol rises above 200 mg/dL, it’s typically considered borderline high; 240 mg/dL or more is classified as high. These elevations create metabolic “roadblocks,” limiting oxygen supply to organs.

Different forms of lipoproteins VLDL, LDL, and HDL-C carry fats like vehicles on a busy highway. When these particles become oxidized or inflamed, they form plaques that can rupture and cause clots. Regular lipid screening, dietary improvements, and lifestyle adjustments remain essential tools for prevention and management.

Causes and Risk Factors

Genetic Factors

Some forms of dyslipidemia are inherited. Primary dyslipidemias arise from genetic defects in lipoprotein metabolism, affecting synthesis, transport, or breakdown of lipids. Disorders like familial hypercholesterolemia or Tangier disease illustrate how a single gene alteration can dramatically alter cholesterol levels. In practice, patients with a strong family history of premature heart disease often prompt me to recommend earlier screening.

Lifestyle Factors

Lifestyle remains a major contributor. Sedentary behavior, high-calorie diets rich in saturated fats, obesity, and excessive alcohol intake can all trigger or worsen dyslipidemia. I’ve noticed that even moderate lifestyle changes such as swapping fried foods for vegetables and walking 30 minutes daily can significantly improve lipid profiles within months.

Medical Conditions and Medications

Certain conditions such as type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, hypothyroidism, and chronic kidney disease predispose individuals to dyslipidemia. Additionally, some medications including beta blockers, thiazide diuretics, and antipsychotics can elevate lipid levels. Clinically, a detailed medication and medical history is often crucial in identifying secondary dyslipidemia.

Environmental and Socioeconomic Influences

While research is limited in this area, it’s clear that dietary accessibility, urbanization, and socioeconomic status influence lipid levels. Populations with limited access to fresh produce or safe exercise spaces often face higher risks, emphasizing that prevention must also address societal factors.

Types of Dyslipidemia

High LDL (Bad Cholesterol)

Elevated LDL is directly linked to plaque formation in arteries . Patients I’ve counseled often underestimate LDL because it doesn’t cause symptoms until advanced disease. Clinically, even modest LDL reductions have been shown to reduce cardiovascular events substantially.

Low HDL (Good Cholesterol)

Low HDL levels reduce the body’s capacity to clear cholesterol, increasing CVD risk . While raising HDL alone isn’t always protective, a comprehensive approach exercise, diet, weight loss is most effective.

Elevated Triglycerides

Triglycerides ≥150 mg/dL are considered high, while levels ≥500 mg/dL can lead to pancreatitis . I’ve seen patients with severe hypertriglyceridemia improve dramatically after structured diet and weight management plans, underscoring the value of lifestyle intervention.

Mixed or Combined Dyslipidemia

When LDL is high, HDL is low, and triglycerides are elevated, it’s termed mixed dyslipidemia. It’s commonly associated with obesity, diabetes, or metabolic syndrome and often requires both lifestyle and pharmacologic strategies.

Secondary Dyslipidemia

Secondary dyslipidemia arises from conditions, medications, or lifestyle factors rather than genetic causes. Identifying the root cause is essential for effective management.

Symptoms and Complications

Common Symptoms

Dyslipidemia is often silent, making routine screening essential. Severe cases may manifest with xanthomas or pancreatitis, but these are rare .

Persistently elevated LDL or triglycerides accelerate atherosclerosis, increasing the risk of coronary artery disease, heart attacks, and sudden cardiac death . Clinically, I emphasize early detection most patients with lifestyle changes and therapy see marked risk reduction.

Atherosclerosis can affect cerebral arteries, contributing to stroke risk. Severe hypertriglyceridemia can cause pancreatitis, while chronic dyslipidemia may impact kidney and liver health .

Early Warning Signs You Shouldn’t Ignore

Subtle signs may include xanthomas, corneal arcus, or a strong family history of premature heart disease. In my practice, these cues often prompt earlier lipid screening before major events occur.

Diagnosis and Screening

Diagnosis relies on fasting or non-fasting lipid panels, measuring total cholesterol, LDL, HDL, and triglycerides .

Typical thresholds:

- LDL ≥160 mg/dL (high risk)

- HDL <40 mg/dL in men, <50 mg/dL in women

- Triglycerides 150–499 mg/dL (high), ≥500 mg/dL (severe)

Age and Risk Based Recommendations

Adults should generally have cholesterol checked every 4–6 years, with earlier or more frequent testing for high-risk individuals.

Referral is warranted for genetic dyslipidemia, severe lipid abnormalities, or poor response to therapy. Early specialist intervention often prevents complications.

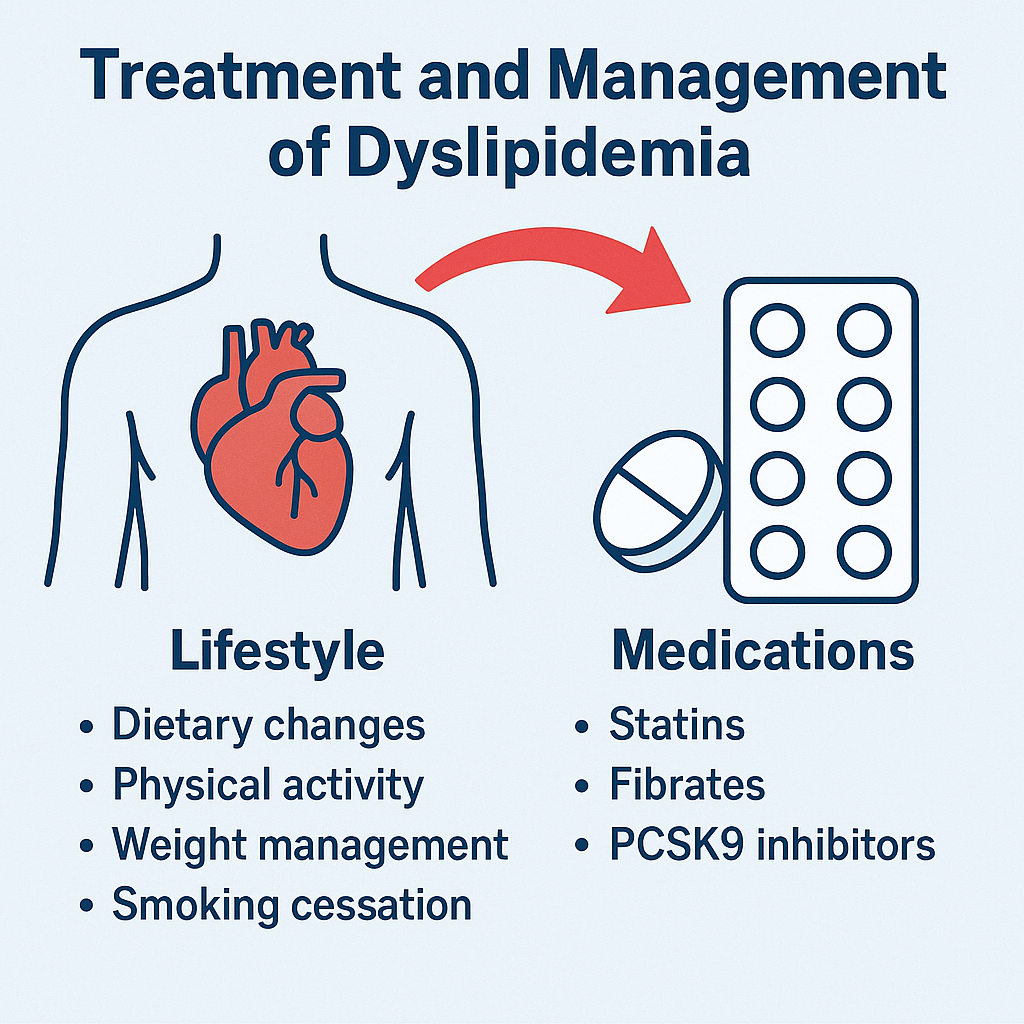

Treatment and Management

Lifestyle Modifications

A diet low in saturated fats, rich in fiber, and balanced in calories improves lipid profiles. For high triglycerides, reducing simple sugars and alcohol is essential .

Exercise and Physical Activity

Aerobic exercise and resistance training lower triglycerides, modestly increase HDL, and improve insulin sensitivity.

While evidence is limited, stress reduction through mindfulness or meditation may support overall cardiovascular health.

Medications

First-line therapy for elevated LDL; they reduce cardiovascular events significantly.

Fibrates and Other Lipid-Lowering Drugs

Fibrates target triglycerides, often combined with statins to reduce combined dyslipidemia (PMC). Other agents include ezetimibe, PCSK9 inhibitors, and bempedoic acid .

Frequent lipid testing allows adjustment of medications and lifestyle strategies. I’ve found patients who track progress closely are more likely to achieve targets.

Prevention

Healthy Eating and Weight Management

Even 5–10% weight loss can significantly improve triglyceride levels and overall cardiovascular risk.

Consistent aerobic and resistance training improves lipid metabolism and heart health.

Avoid smoking, excessive alcohol, and uncontrolled diabetes or hypertension these amplify dyslipidemia risk.

Community and Workplace Initiatives for Heart Health

Promoting accessible fitness programs, healthy cafeteria options, and educational campaigns helps reduce population-level lipid disorders, although specific peer-reviewed data is limited.

Living with Dyslipidemia

Tracking Lipid Levels

Routine follow-up and patient engagement improve adherence. In my experience, patients who maintain logs of diet, exercise, and lab results are more successful in controlling dyslipidemia.

Long-Term Heart Health Tips

Lifelong commitment to healthy lifestyle and monitoring is key. Even modest changes early in life yield substantial long-term benefits.

Coping Strategies and Mental Health

Living with a silent condition can be stressful. Counseling, support groups, and education about heart-healthy habits can reduce anxiety and empower patients.

Patient Stories or Case Studies

For example, one patient with high triglycerides and a family history of heart disease reversed most of the risk through dietary changes, exercise, and medication adherence over six months a testament to the effectiveness of a combined approach.

Medically reviewed by

Medically reviewed by