What is Pediatric Stroke?

A pediatric stroke is a neurological event occurring in children under 18 years of age. Unlike adults, children may not show classic focal neurological deficits. In neonates (first 28 days of life), strokes can be ischemic (blocked blood flow) or hemorrhagic (bleeding in the brain). Early signs in infants are often subtle, including seizures, irritability, poor feeding, or unusual postures, making early recognition challenging. Prompt identification is critical to prevent long-term cognitive and motor impairments.

Differentiation from Adult Stroke

Children and adults differ in stroke etiology and presentation. In children, strokes are often caused by congenital heart defects, clotting disorders (thrombophilia, sickle cell disease), or vascular abnormalities (arteriopathies, venous sinus thrombosis). Adolescents may display sudden hemiparesis or speech changes, whereas infants may appear lethargic or feed poorly. Despite children’s enhanced neuroplasticity, long-term behavioral, cognitive, and motor deficits can still occur, impacting daily life, schooling, and family functioning.

Epidemiology: Neonates vs Older Children

Pediatric stroke is rare but serious. Incidence estimates:

- Neonatal stroke: ~1 in 2,300–5,000 births, higher in perinatal complications.

- Childhood stroke: 2–13 per 100,000 children per year.

Perinatal risk factors include low oxygen, coagulation abnormalities, or birth injuries. Mortality ranges from 10–25%, and over half of survivors experience long-term morbidity.

Global Burden of Pediatric Stroke

- According to the GBD 2021 study, there were 310,133 new pediatric stroke cases in 2021 among children and adolescents under 20 years.

- That year, there were 24,807 deaths and 2,414,655 disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) lost due to stroke in this age group.

- The age-standardized incidence rate (ASIR) for stroke in children/adolescents was 11.8 per 100,000.

- The age-standardized DALY rate (ASDR) was 93.9 per 100,000, and the mortality rate (ASMR) was 1.0 per 100,000 in 2021.

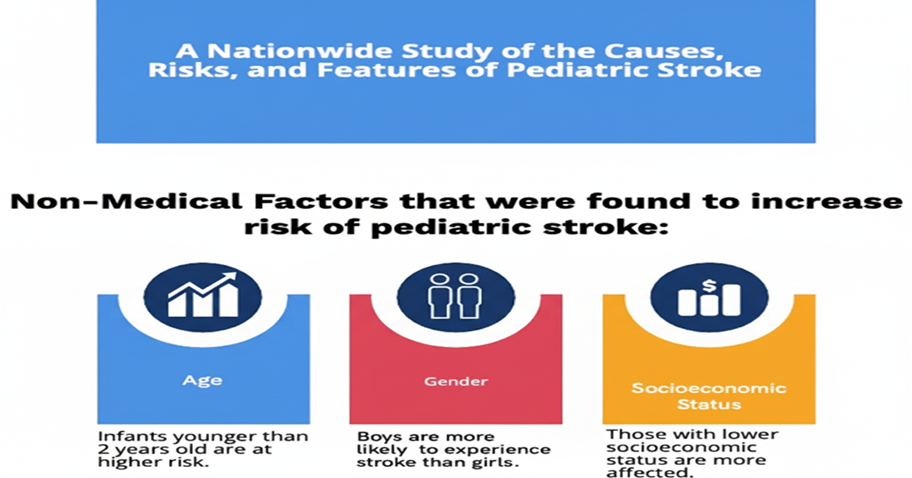

- A large share of the burden remains in low‑ and middle‑sociodemographic index (SDI) regions: in 2021, 81.6% of incident cases, 90.2% of DALYs, and 92.7% of deaths occurred in these regions.

- Importantly, non-optimal (environmental) temperature was identified as a leading modifiable risk factor for pediatric stroke DALYs and deaths.

Types and Pathophysiology

Ischemic Stroke

Arterial ischemic stroke (AIS) occurs when a blood clot, arterial narrowing, or vascular abnormality blocks blood flow to part of the brain, causing cell injury or death. AIS is the most common type of ischemic stroke in children.

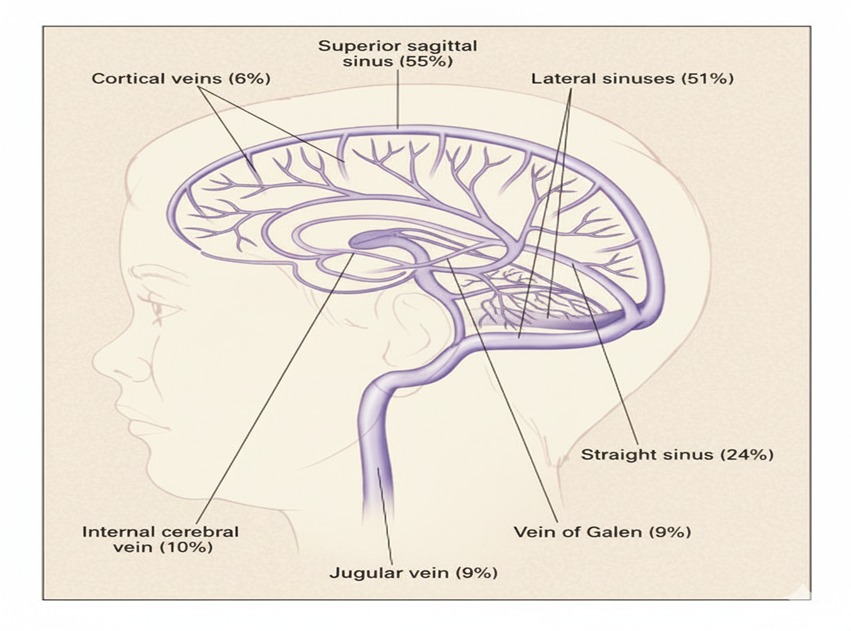

Cerebral sinovenous thrombosis (CSVT) occurs when blood clots form in the brain’s venous sinuses, impairing drainage. This can increase intracranial pressure or cause venous infarction. Children may present with headache, seizures, or altered consciousness. Arteriopathy, an abnormality of the arteries, is a frequent mechanism in children, unlike adults where cardioembolic strokes are more common.

Hemorrhagic Stroke

Hemorrhagic strokes include intracerebral hemorrhage (bleeding into brain tissue) and subarachnoid hemorrhage (bleeding around the brain). Common causes include vascular malformations (like AVMs), trauma, and coagulation disorders. Symptoms often appear suddenly, such as severe headache, vomiting, decreased consciousness, or focal neurological deficits. Pediatric hemorrhagic strokes account for nearly half of childhood strokes a higher proportion than in adults.

Age-Based Differences

Neonates (20 Weeks Fetal Life – 28 Days)

Symptoms are subtle, including seizures, apnea, or feeding difficulties. Causes often include perinatal asphyxia, coagulation abnormalities, or maternal factors. Incidence: ~1 in 2,300–5,000 live births.

Older Children (1 Month – 18 Years)

Presentations are more classic: focal neurological deficits, headaches, or altered mental status. Underlying causes often include arteriopathies, congenital heart disease, sickle cell disease, or trauma. Recognizing age-specific differences is crucial for accurate diagnosis, timely management, and prognosis.

Risk Factors and Etiology

Neonatal Stroke

Neonatal strokes often arise from factors that disrupt blood flow to the newborn brain:

- Perinatal Asphyxia: Reduced oxygen at birth injures delicate cerebral vessels.

- Cardiac Disorders: Congenital or acquired heart defects can cause embolic events.

- Maternal Factors: Eclampsia, chorioamnionitis, or placental problems increase risk.

- Coagulation Abnormalities: Thrombophilia, platelet disorders, or polycythemia predispose infants to clots.

Clinical signs are subtle, including seizures, apnea, or poor feeding.

Childhood Stroke (1 Month–18 Years)

In older infants and children, arteriopathies dominate:

- Arteriopathies: Focal cerebral arteriopathy and moyamoya disease

- Sickle Cell Disease: Causes vasculopathy and arterial injury

- Congenital or Acquired Heart Disease: Cardioembolic strokes

- Infection and Inflammation: e.g., varicella-associated arteriopathy

- Trauma and Metabolic/Genetic Disorders

Children often present suddenly with weakness, speech difficulties, or coordination problems.

Diagnostic Evaluation

Imaging

- MRI / DWI: Gold standard for detecting acute ischemic stroke; shows location and extent.

- MRA / CTA: Evaluates arterial and venous structures; MRA preferred to avoid radiation.

- CT Scan: Rapidly assesses hemorrhage or large infarcts; useful in unstable patients.

Laboratory and Ancillary Tests

- Coagulation Panel / Thrombophilia Workup: Detects protein C/S deficiency, factor V Leiden, antiphospholipid antibodies.

- Cardiac Evaluation: Echocardiography and ECG detect structural heart defects or emboli.

- Inflammatory and Infectious Markers: CRP, ESR, blood cultures, serologies.

- Lumbar Puncture: If CNS infection or inflammation suspected.

Acute Management

Stabilization

- Airway, Breathing, Circulation (ABC): Ensure oxygenation and hemodynamic stability.

- Seizure Control: Benzodiazepines and antiepileptic drugs prevent further brain injury.

- Intracranial Pressure Monitoring: Use clinical signs, imaging, or invasive devices; manage with head elevation, osmotic therapy, and sedation.

Long-Term Management and Rehabilitation

- Early, repetitive, task-specific therapy restores movement and strength.

- Addresses language, memory, attention, and learning challenges.

- Regular neurological follow-up; antiepileptic medications if seizures occur.

- Counseling, family education, and peer groups reduce stress and improve rehabilitation adherence.

- Structured return to school with academic accommodations; Individualized Education Plans (IEPs) support learning and safety.

Treatment Strategies

Antithrombotic Therapy (Anticoagulation vs Antiplatelet)

Prevents new clots or extension. Anticoagulation (heparin, LMWH) for venous or cardioembolic strokes; antiplatelets (aspirin) for arterial strokes without cardiac source.

Thrombolysis: Selection Criteria & Controversies

Tissue Plasminogen Activator may be used in select acute ischemic strokes within a narrow window; pediatric use is limited and controversial.

Endovascular Therapy in Children

Catheter-based clot removal or vessel repair; considered for large vessel occlusion when thrombolysis is inadequate.

Management of Hemorrhagic Stroke

Surgery to evacuate bleeds or repair malformations, blood pressure control, ICP management, and supportive care.

Stroke Pathways and Pediatric Stroke Codes

Hospital protocols ensure rapid recognition, imaging, and treatment through multidisciplinary teams.

Complications and Outcomes

Recurrence Risk

Highest in first year; children with arteriopathies, cardiac disorders, or prothrombotic conditions are most at risk.

Long-Term Neurologic Deficits

Hemiparesis, motor coordination difficulties, and seizures; early rehabilitation improves outcomes.

Cognitive and Behavioral Outcomes

Learning difficulties, attention problems, behavioral changes; cognitive therapies enhance school and social integration.

Quality of Life Considerations

Physical, cognitive, and social limitations; multidisciplinary follow-up and individualized planning improve well-being.

Prevention Strategies

Primary Prevention for High-Risk Populations

Management of sickle cell disease, congenital heart disease, and coagulation disorders reduces first stroke risk.

Secondary Prevention

Antithrombotic therapy, revascularization procedures in moyamoya disease, and close neuroimaging follow-up prevent recurrence.

Vaccination and Infection Control

Prevent infections like varicella zoster; maintain immunizations and promptly treat systemic infections.

FAQ’s

Q. What is pediatric stroke?

A. A pediatric stroke is a neurological event in children under 18 years of age caused by either a blockage of blood flow (ischemic stroke) or bleeding in the brain (hemorrhagic stroke). It can occur in newborns (neonates) or older children and requires prompt recognition to prevent long-term cognitive, motor, and behavioral impairments.

Q. What are the symptoms of a child having a stroke?

A. Symptoms vary by age:

- Neonates: Seizures, unusual postures, irritability, poor feeding, lethargy, apnea.

- Older children: Sudden weakness or numbness on one side, trouble speaking, facial drooping, headache, vomiting, or loss of coordination.

Q. What does a stroke look like in a baby?

A. In babies, strokes often present subtly. Signs include seizures, poor feeding, unusual body positions, irritability, or periods of unresponsiveness. These can easily be mistaken for common infant issues, so high vigilance is needed.

Q. How long does it take to recover from pediatric stroke?

A. Recovery varies depending on stroke severity, type, and age. Some children regain significant function within months, while others may require years of therapy. Early intervention and consistent rehabilitation are key to better outcomes.

Q. Are there conditions during pregnancy that increase the risk of pediatric stroke?

A. Yes, Maternal health issues such as preeclampsia, eclampsia, infections, or placental complications that reduce oxygen delivery can increase the risk of neonatal stroke. Prenatal care and management of maternal conditions are crucial.

Conclusion

Pediatric stroke is a complex and heterogeneous condition with unique challenges compared to adult stroke. Early recognition is critical, as neonates often present with subtle signs while older children may show more classic neurological deficits. Risk factors vary by age, with perinatal, maternal, and hematologic contributors predominating in neonates, and arteriopathies, cardiac disorders, and genetic conditions in older children.

Multidisciplinary management including acute stabilization, targeted therapies, rehabilitation, and psychosocial support is essential to optimize outcomes. Advances in neuroimaging, biomarkers, and pediatric-specific interventions are improving diagnosis, individualized treatment, and long-term prognosis.

Medically reviewed by

Medically reviewed by