Introduction

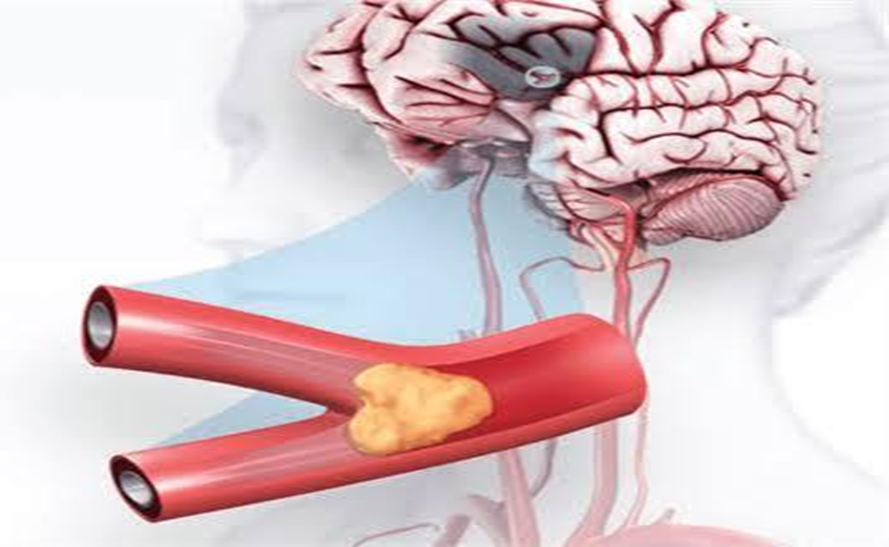

An ischemic stroke occurs when the blood flow to a part of the brain is blocked or reduced, preventing vital oxygen and nutrients from reaching brain cells. This blockage usually happens when a blood vessel becomes obstructed by a blood clot or fatty plaque that develops on the vessel walls. About 87% of all strokes are ischemic strokes.

This condition is considered a life-threatening medical emergency. If enough brain cells die, it can lead to brain damage, long-term disability, or even death. The loss of body functions depends on which site of the brain’s blood vessels is affected. Sometimes, pressure from bleeding or leaks in nearby small vessels can worsen the complications. That’s why it’s crucial to call 911 or your local emergency services right away when someone shows stroke symptoms doing so quickly can reduce lasting effects and improve the chances of recovery.

Fortunately, effective treatments and medical treatment approaches today have made it possible to prevent disability and reduce deaths. There are fewer cases now compared to the past, thanks to emergency medical help and rehabilitation that improve survival rates. I still remember observing a patient during my clinical rotation how quick treatment and medical emergency protocols could literally save a life within minutes. Every second counts because brain tissue starts to die almost immediately.

Prevalence and Incidence

Global Prevalence:

Approximately 68 million people had ischemic stroke in 2020.

Global Incidence:

About 11.71 million new cases occurred globally in 2020.

In United States:

Stroke ranks among the top causes of death in the United States and is a significant contributor to severe disability in adults. Among all types of strokes, the ischemic type is the most common, accounting for about 80%–87% of cases. Every year, more than 795,000 people in the United States have a stroke.

Types of Ischemic Stroke

When it comes to ischemic strokes, not all cases are alike. They are subdivided into two main categories thrombotic and embolic depending on where the blood clot originates and how the process happens in the brain. During my training, I once observed a case where identifying the exact type of stroke using the TOAST system short for the Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment, a multicenter trial made a major difference in the treatment plan. This system divides ischemic strokes into subtypes such as:

- Large-artery infarction

- Small-vessel (lacunar) infarction

- Cardioembolic infarction

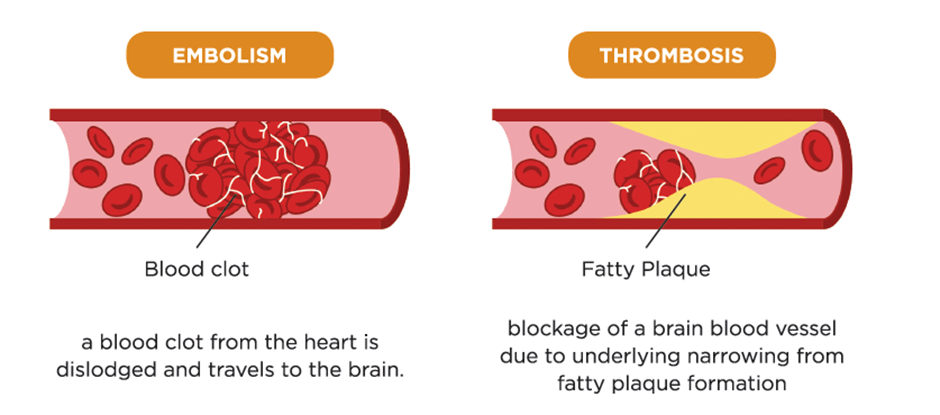

Thrombotic Stroke

A thrombotic stroke develops when a blood clot forms directly within a vessel that supplies blood to the brain. This process, known as thrombosis, typically occurs in the large arteries like the carotid, vertebrobasilar, or cerebral arteries which may already be narrowed by atherosclerotic lesions, plaque, or fatty buildup on the walls.

Key factors and characteristics include:

- Common in older persons with high cholesterol or diabetes.

- Can develop gradually over hours or days.

- Often occurs during sleep or early morning.

- Symptoms can appear suddenly or mildly, but require quick medical attention.

Embolic Stroke

An embolic stroke occurs when a clot or debris travels from another part of the body, often the heart, and becomes stuck in a blood vessel in the brain. This condition, known as embolism, is often linked to:

- Heart surgery or cardiogenic emboli.

- Atrial fibrillation an abnormal rhythm where the upper chambers of the heart do not beat effectively.

Because the embolus moves rapidly through the bloodstream and blocks a vessel without warning, it’s one of the most life-threatening types. Around 15% of all embolic strokes occur in people with atrial fibrillation, highlighting its importance in stroke prevention.

Causes and Risk Factors of Ischemic Stroke

From my medical and research experience, ischemic stroke stands out as one of the most common strokes. It occurs when ischemia a loss of blood flow damages brain cells. The main cause is often a blood clot that blocks an artery supplying the brain. These clots may:

- Form directly in the blood vessels of the brain (thrombosis).

- Travel from another part of the body, such as the heart, causing an embolism.

When either process happens, the flow of blood is reduced, and cells begin dying due to lack of oxygen and nutrients.

Major Health Related Causes

Certain health conditions increase the risk of ischemic stroke:

- Atherosclerosis: The hardening of arteries as plaque (a sticky substance made of cholesterol, fat, and other substances) builds up along the artery walls.

- Clotting disorders or hypercoagulability: These make the blood thicker, raising the chance of clot formation.

- Microvascular ischemic disease: This affects smaller blood vessels, leading to lacunar infarcts tiny strokes deep within the brain.

- Inflammation or infection in the blood vessels or arteries may also block blood flow and worsen ischemic damage.

Heart-Related Conditions

The heart plays a key role in ischemic stroke:

- Atrial fibrillation (an irregular rhythm) can cause blood to pool and form clots that travel to the brain.

- Heart valve diseases and heart defects like atrial septal defects or ventricular septal defects (small holes in the chambers of the heart) may allow clots to move into the bloodstream.

- Sickle cell disorder, myocardial infarction, and coronary artery disease can also disturb flow and increase risk through inflammation, infection, or damage to heart muscle.

Lifestyle and Personal Risk Factors

Beyond medical causes, certain lifestyle habits and personal traits raise the likelihood of an ischemic stroke:

- Smoking, excessive alcohol use, or recreational drug use.

- Obesity, lack of exercise, or a sedentary lifestyle.

- High blood pressure, high cholesterol, or diabetes.

- Uncontrolled coronary artery disease or heart valve diseases.

- Family history of stroke or heart disease.

- Age (especially older men and women).

- Ethnic background African-Americans and Caucasians show differing risk levels.

- Transient ischemic attacks (TIAs) or “mini-strokes,” which serve as warning signs for a major stroke.

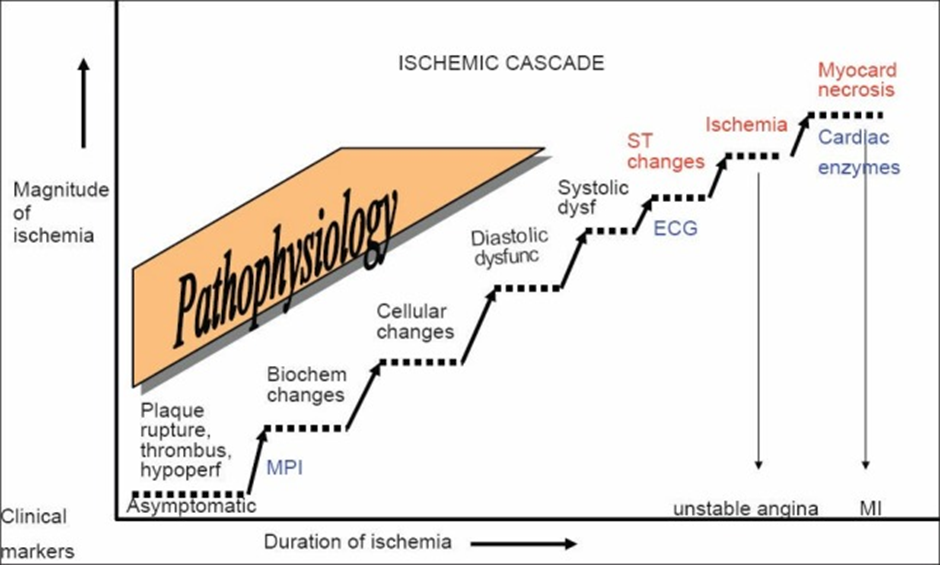

Pathophysiology and Cellular Changes

When an acute ischemic stroke occurs, a vascular occlusion blocks normal blood flow in the cerebral tissue, cutting off oxygen and nutrients to the brain. This blockage, often caused by a thromboembolic disease, triggers a series of physiological pathways that harm the neuronal cells. Within minutes of the onset, the affected territory experiences ischemia, leading to cell hypoxia and depletion of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) the main energy source that keeps ionic gradients balanced across the membrane.

Without ATP, sodium-potassium plasma pumps stop functioning, resulting in depolarization, intracellular swelling, and cytotoxic edema. The neurons in the core area quickly die, while the penumbra a viable but time-sensitive zone remains salvageable for a few hours through collateral supply and limited perfusion.

Ion Imbalance and Excitotoxicity

Inside these cells, sodium and calcium ions flood in, disturbing ion homeostasis and activating neurotransmitters such as glutamate that bind to N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) and other excitatory receptors. This overactivation produces free radicals, arachidonic acid, and nitric oxide, causing toxicity and damaging proteins, membranes, and neuronal structures. As the ischemia-induced process continues, degradative enzymes worsen the necrotic and apoptotic death of cells.

Inflammation, driven by cytokines, microglial, astrocytes, and macrophages, adds to the injury, leading to microcirculatory compromise and leukocyte infiltration around the infarcted tissue. Over days to weeks, vasogenic edema, mass effect, and extracellular fluid accumulation increase pressure within the vasculature.

Chronic Changes and Tissue Remodeling

Later, as part of chronic evolution, resorption and parenchymal changes like encephalomalacia, cystic degeneration, and cerebrospinal density loss occur. This focal pathology reflects both cellular acidosis and anaerobic glycolysis, where pyruvate converts into lactate, releasing protons (H+), lowering pH, and raising pCO2, all contributing to lactic acidosis. Having observed similar cases during clinical trials, it’s clear that small infarct cores with larger penumbral sizes respond better to treatment a point of great medical interest in managing stroke recovery and preventing further neuronal death.

Symptoms and Early Warning Signs

Often, these symptoms happen suddenly and may affect one side of the face, arm, or leg, causing weakness or paralysis. Some people experience aphasia, trouble speaking, loss of speech, or slurred, garbled, or dysarthria. Muscle control can also be lost, leading to coordination problems, clumsiness, or ataxia.

Other signs may include changes in the senses, such as vision, hearing, smell, taste, or touch. You might notice blurry or double (diplopia) vision, dizziness, vertigo, nausea, vomiting, neck stiffness, or sudden severe headaches. Mood swings, personality changes, confusion, or agitation may also occur, along with memory problems like amnesia. Seizures, passing out, fainting, or even coma can happen in acute cases.

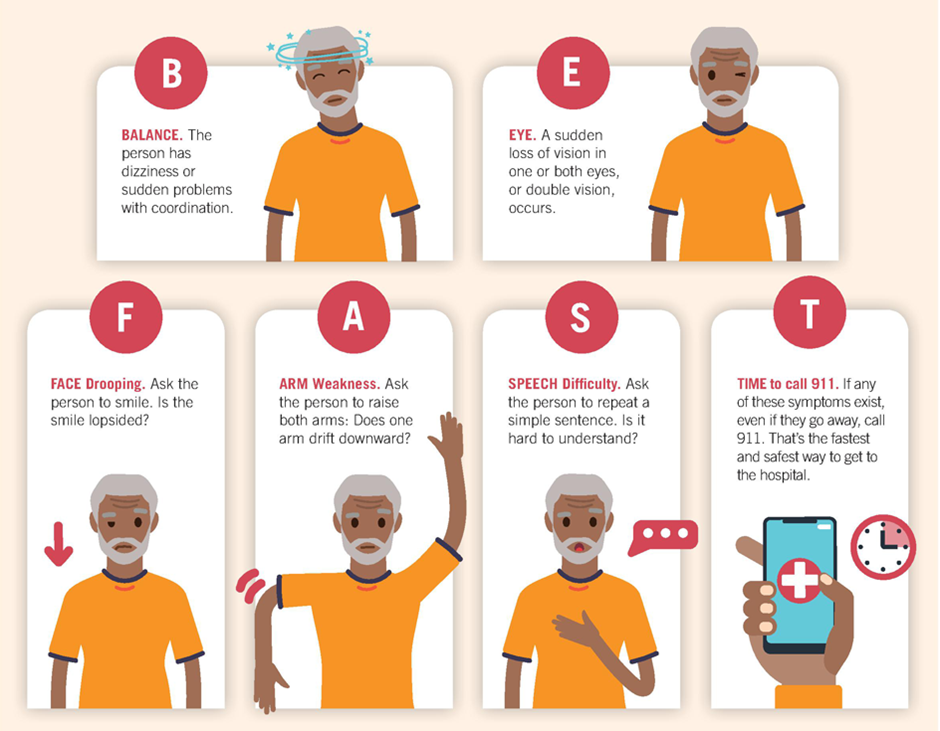

A helpful way to recognize warning signs quickly is the F.A.S.T. test, based on the acronym BE FAST:

- Balance – Watch for sudden loss of balance.

- Eyes – Look for sudden changes in vision.

- Face – Check for a droop when smiling.

- Arms – Ask the person to raise both arms; one may sag or drop.

- Speech – Notice slurred, strange, or trouble choosing words.

- Time – Call for help immediately; every minute counts.

Diagnosis and Assessment

A healthcare provider begins with a neurological exam and a thorough physical assessment, reviewing the patient’s history, listening to the heart, and checking blood pressure to evaluate the nervous and cardiovascular systems. This initial evaluation helps detect weakness, paralysis, coordination issues, speech difficulties, and other stroke effects.

Key Diagnostic Methods:

- Neurological Exam: A physical assessment to evaluate muscle strength, coordination, reflexes, speech, vision, and sensation to detect stroke effects.

- CT Scan (Computed Tomography): Uses X-rays to produce detailed brain images. Can detect bleeding, tumors, abscesses, or ischemic areas. Contrast dye can highlight blood vessels (angiography).

- MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging): Uses magnetic fields and radio waves to detect damaged tissue, hemorrhages, and disrupted blood flow. Variants like magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) provide detailed views of arteries.

- Electroencephalogram (EEG): Measures electrical activity in the brain to detect seizure activity or abnormal neuronal patterns associated with stroke.

- Electrocardiogram (EKG): Records the heart’s electrical activity to detect irregular rhythms like atrial fibrillation, which can form clots leading to stroke.

- Blood Tests: Check for hyperglycemia, hypoglycemia, metabolic abnormalities, infection, or clotting disorders. Helps identify conditions that increase stroke risk or complicate treatment.

- Carotid Ultrasound: Uses sound waves to examine the carotid arteries in the neck, detecting plaque buildup, fatty deposits, and narrowing that can block blood flow to the brain.

- Cerebral Angiogram: Involves inserting a thin catheter, usually through the groin, into cerebral or vertebral arteries. Dye is injected to make arteries and veins visible on X-rays, detecting blockages or abnormalities.

- Echocardiogram: Uses sound waves to image the heart and detect clots that may have traveled to the brain, causing a stroke.

Prevention and Risk Reduction

Preventing Ischemic Stroke Through Lifestyle Choices

- Nutritious diet: Include a variety of fresh fruits, vegetables, whole grains, low-fat dairy, and fish two to three times weekly. Limit foods high in cholesterol such as burgers, cheese, and ice cream.

- Maintaining healthy weight: Track progress using BMI and waist-to-hip measurements. Being overweight or obese increases stroke likelihood, so even modest weight loss can improve health outcomes.

- Regular exercise: Participate in moderate-intensity aerobic activities, like brisk walking, for at least 30 minutes, five times per week. For children and adolescents, aim for 1 hour of daily activity. Initiatives like the “Live to the Beat” campaign provide guidance and motivation.

- Avoid tobacco and moderate alcohol: Smoking sharply elevates stroke risk, but quitting can reduce it almost immediately. Limit alcohol intake to one drink per day for women and two for men.

- Managing medical conditions: Keep blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood sugar within recommended ranges. Adhere to prescribed medications and collaborate closely with healthcare providers. Healthy lifestyle practices, along with proper medication adherence, are critical in lowering stroke risk, especially after a transient ischemic attack (TIA).

Addressing High Risk Factors

For individuals with vascular or cardiac conditions, targeted interventions are often necessary to prevent stroke recurrence.

- Blood pressure management: Systolic readings above 160 mm Hg or diastolic above 90 mm Hg significantly raise stroke risk. Consistent monitoring and treatment can protect even older adults.

- Cholesterol control: Statin therapy effectively reduces cholesterol, lowering the risk of stroke and heart attacks.

- Atrial fibrillation management: Patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation may require anticoagulants like warfarin, while those at lower risk could use aspirin or platelet inhibitors such as clopidogrel. Treatment plans are individualized based on patient history and risk factors.

- Platelet inhibitors: Medications like ticlopidine or dipyridamole may be prescribed if aspirin is unsuitable. While these drugs reduce stroke risk, potential side effects include diarrhea or, rarely, bone marrow suppression.

Surgical Intervention: Carotid Endarterectomy

Surgery may be recommended for patients with significant carotid artery narrowing when medication alone is insufficient. Decisions depend on stenosis severity, symptoms, and procedural risk.

- Symptomatic stenosis: Patients with 70–99% narrowing usually benefit most from surgery.

- Asymptomatic stenosis: Surgery is considered selectively, following a careful evaluation of risks.

- Imaging guidance: Ultrasound and MRI scans help identify suitable candidates.

- Personalized evaluation: Factors such as age, existing health conditions, stenosis location, and surgical expertise influence the expected benefit.

Prognosis and Outlook

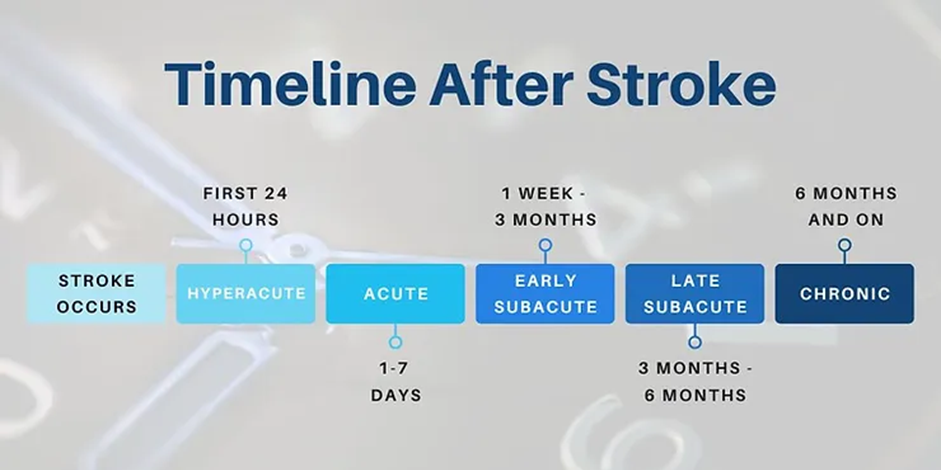

The prognosis after an ischemic stroke in young adults can vary widely depending on several factors. Understanding the long-term outcomes is crucial for both patients and physicians, as it helps in optimizing secondary prevention strategies and setting realistic expectations. Early detection and accurate prognostic information play a key role in determining functional limitations, mortality risk, and the potential for moderate-to-severe disability. In my experience, patients who are informed about their prognosis often engage better in rehabilitation and recovery planning.

The impact of an ischemic stroke is not only physical but also social and emotional, affecting the percentage of patients who regain independence. Stroke subtype, initial severity, and cardiovascular risk factors significantly determine outcomes. Some patients recover quickly in the first three to six months, while others may require long-term support, depending on their unique situation.

Clinical studies, including randomized trials like Tirilazad Mesylate (RANTTAS) with n=279 patients, have helped determine the frequency, severity, and impact of these complications. Using logistic regression techniques, researchers found significant correlations between early functional disability measured by Barthel Index, Glasgow Outcome Scale, and the odds ratio (OR) of adverse outcomes. For instance, mortality rates at 3-months were observed to be 14%–51%, with deaths attributed primarily to serious medical complications or cerebral infarction extension.

Recovery after an ischemic stroke can be slightly slower or more challenging for some, but understanding which areas of the brain are affected, how quickly treatment started, and overall health can improve outcomes. In my practice, careful monitoring of changes, early intervention, and ongoing assessment of functional limitations has been essential for supporting patients’ long-term recovery.

Conclusion

Ischemic stroke remains a leading cause of death and disability, yet it is highly preventable with timely intervention and proactive management. Understanding the types of ischemic stroke, recognizing early symptoms through tools like the FAST test, and identifying modifiable risk factors are essential steps for both patients and healthcare providers.

Prevention relies on a multi-layered approach: adopting healthy lifestyle habits, managing medical conditions like hypertension, diabetes, and atrial fibrillation, and utilizing surgical or pharmacological interventions when appropriate. Early recognition, rapid medical care, and personalized treatment strategies significantly improve outcomes and reduce long-term complications.

Medically reviewed by

Medically reviewed by